“Grief is a calamity, weakening and throwing a person into disarray.” — My grandfather after the loss of his wife, my grandmother.

As a child, one of my recurrent prayers was to ask God for long life and prosperity. But something my 5-year-old self failed to consider is that a long life comes with a bootload of grief.

If you’re “lucky,” your disasters are paced, and you get a blindsiding event once every three or more years. However, if you’re like my grandfather, you have periods of quietness and boom! — several disasters everywhere, all at once, without pause.

How else do you explain him losing his wife [my grandma] of 58 years and his first child [my aunt] within six months of each other? Naturally, in life’s cruel irony, this was followed by a health scare for him and, by extension, the family.

There’s a scene in the movie “The International” where Detective Louis Salinger, played by Clive Owen, interrogates a former die-hard communist, Colonel Wexler. In their meeting, Salinger says, "You lost your wife to betrayal, your daughter to suicide, and when the [Berlin] wall fell, your whole life fell apart with it.” Colonel Wexler then replies: "We can't control the things life does to us. They are done before you know it, and once they are done, they make you do other things until, at last, everything comes between you and the man you wanted to be."

Something about this line makes me empathise with older adults. Sometimes, life keeps chipping away at you until you become a different person from the ideals of your younger self.

In other cases, life completely overwhelms you until you no longer have the will to participate.

In the Fourth State of Matter essay, a woman tries to recover from depression after losing her elderly mother and husband of sixty years within a year of each other. She decides to visit her only child in America, and he tries to cheer her up by taking her to art galleries and showing her “American art.” During her stay, her son, Chris — her last leg of defence against this cruel world — is killed by a disgruntled gunman at the University where he lectures. Surprisingly, Chris' mother doesn't react. In fact, she weathers the news with a dignified appearance and, from the outside, appears to carry herself well. Then she quietly packs her bags, returns home to Germany, and kills herself “without further words or fanfare.”

After overcoming the shock of that paragraph, I found myself asking: What tethers you to this earth when your family tree is at the point where there are now “enough people in the afterlife to make a family picture?”

Where do you find hope when the light goes out of your life?

Pushed against the wall by the questions in my mind, I turn to the internet for answers. One, two, three, and too numerous to count Google-search rabbit holes away, I land on the English poet John Keats.

In particular, I find myself drawn to his idea of negative capability, which he describes as the ability to accept “uncertainties, mysteries, and doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.”

That is, resisting the urge to have an explanation for everything.

So, I try to tolerate ambiguity and fight the need to protect myself through understanding and — by extension — control.

The first few days pass without event; however, I am back to obsessing and itching for answers as time passes. Am I supposed to accept that I’ll never see my grandma smile again? Do I just live with the fact that no one will ever call me “T-bobo-T again?” [The nickname only my aunt and grandmother call me by].

There’s only so much I can take before I consider throwing the idea of negative capability out of the window. I think about my grandfather in the weeks after my grandma passed. Specifically, I think of the nights spent outside his room, hearing him scream as if haunted by a ghost.

I can't help but reflect that at 83, my grandfather has lost both parents, one brother, one wife, two children, and numerous friends. I also can't help but observe how this most recent upheaval has changed him.

It's in the little things like being unable to approach his wife's [my grandmother's] old room. It's also in the silence that permeates the house when he mistakenly calls out for my grandmother.

But there are also big things, like his rapid weight loss, even though no one ever mentions it out of politeness. There's also the loneliness, he confesses to me in hush tones, of “not having anyone who understands what he's passing through.” The type of loneliness that occurs when [most of] the people who have known you the longest are dead.

At my grandmother's funeral, I catch my grandfather constantly staring into space, as if — I imagine — he's trying to dream up his wife back to life. Throughout the event, I notice a more mellow man in the place of the once boisterous, on-top-of-the-world hilarious grandpa I know. Sorrow has flattened him; what makes him so personable seems lost.

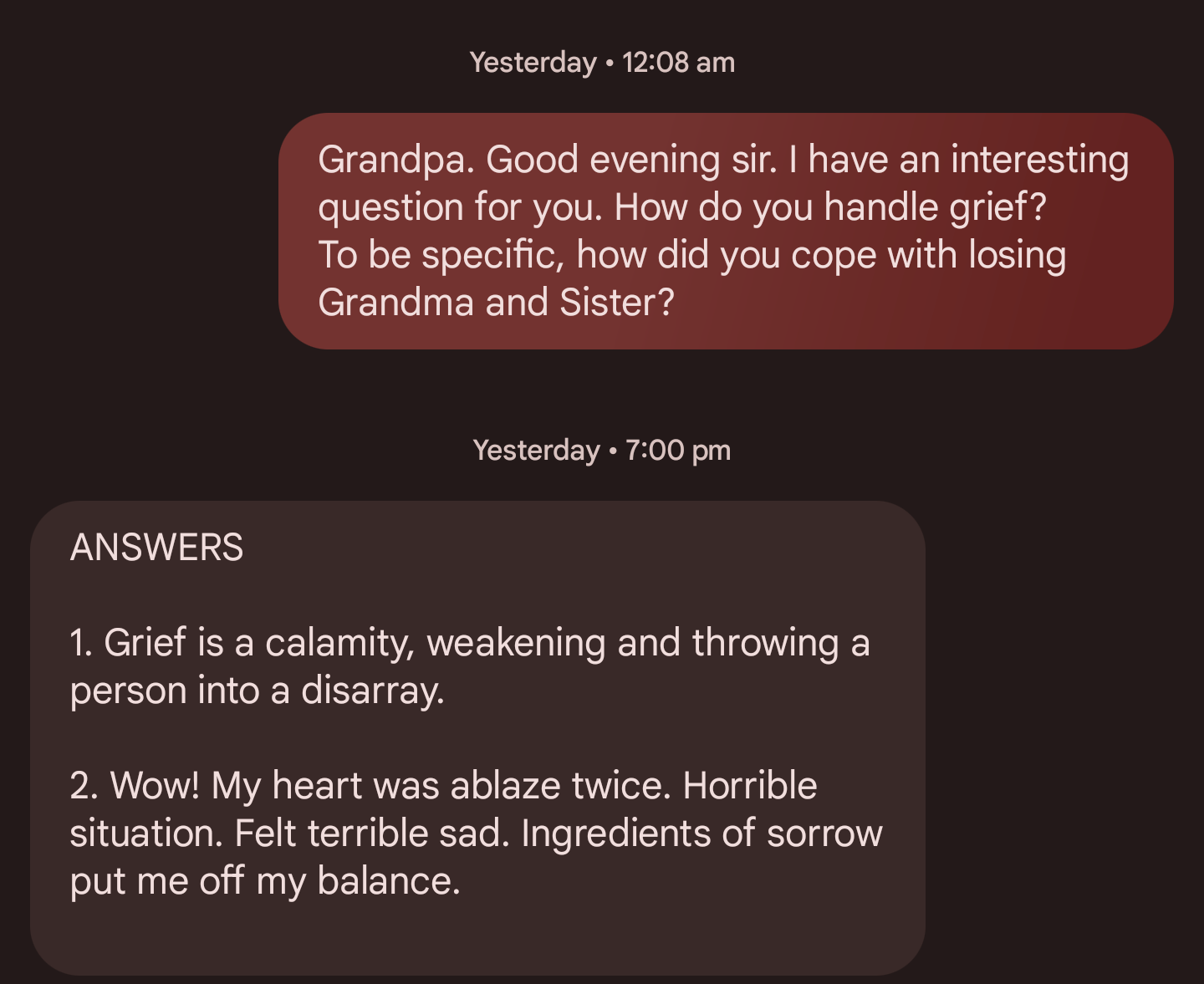

One day, at the beginning of a new month, when I don't get my usual “Happy New Month” text from my grandmother, reality hits me. The finality that I will never hear from her again strikes me out of the blue. I am reminded of the whiplash that is death. Consumed by my private agony, I reach out to my grandpa to ask how he’s handling his grief.

His answers throw me off balance. My mind finds similarities between his response and those of American writer and essayist Joan Didion after the simultaneous loss of her husband and daughter.

But there’s also a difference: My grandfather says he can't write about his grief, while Didion wrote to interrogate her grief.

"I write entirely to find out what is on my mind, what I'm thinking.” — Joan Didion.

Slowly but surely, my centre can’t hold, and like Didion, the questions — and the need for an explanation — come back to haunt me.

So, I ask a friend in their late twenties how they handle grief. They reply that time helps you live better with grief.

I find the idea bitter-sweet: time gives you grief, and time also takes away grief from you.

My brain tells me that making friends with younger people and rediscovering your sense of awe can help with grief. Why do you think this? I ask of no one in particular.

My mind surfaces a quote that says the best definition of youth is “life yet untouched by tragedy”, — meaning that young people, since untainted by grief, are still optimistic about the world. Not satisfied with this answer, I find myself going in circles without closure.

So, I call my grandpa to answer the second part of my question. On the call, I ask: Grandpa, how do you, in particular, navigate grief?

The answer is simple, he replies. You just keep moving forward, one leg after the other, day after day, year after year. What else can you do?

There's silence on my side of the line, after which he asks if I'm still there. “Yes, I reply,” with a defeated sigh.

After the call ends, I go to pray. On the spot, I update my prayer request. I ask God not for long life and prosperity but for amnesia and the strength to keep moving when more grief comes knocking on my door.

A few notes:

1) I took the title of this essay from CS Lewis’s famous book, A Grief Observed.

2) Moyo read the first draft and gave me detailed pointers for thinking about the story. He also shared this heart-wrenching essay on grief that helped with guidance.

3) Nana came in with conversations and questions that helped to refine the writing.

4) Then Ope and Ruka came in, guns blazing, with helpful edits that helped to move the writing forward. Any typos or awkward sentences are strictly mine because I published without informing them.

5) Toheeb ironed out a few kinks I missed because I was sick of looking at the draft.

6) Omeiza had valuable comments on the final draft that made me move a few things around and expand my language and sentences.

7) Biola, the loml, read all versions of this draft. She also listened to my rants and recorded the call with my grandfather for me. Thank you!

8) I initially started writing this draft as a way to explain that life has a lot of disasters baked into it. I had numerous examples to show, but while writing, I realised it was overwhelming to list them all. Here are a few I found:

There’s this tweet about how this person lost her dad, her job, and her business within a year.

Mollie Kyle from The Killers of Flower Moon, whose family was killed because of their [oil] money.

American writer and essayist Joan Didion, after the simultaneous loss of her husband and daughter within a year of each other.