A Few Thoughts on Quality of Problems

There are better quality of problems everywhere for those with the eyes to see

A few days ago, I stumbled upon a profound insight about human progress that's been living rent-free in my head since then. It's called the blue dot effect, and it goes something like this:

’The more we solve our problems, the more we widen the definition of “problem” so that our number of problems remains constant. So don’t expect a life without problems. Progress doesn’t mean reducing your quantity of struggles but increasing their quality. The goal of life is to trade bad problems for better ones.

I love this framing of “problem,” as it helped me unspool several seemingly unrelated mental yarns about progress that had been idling in my head.

Here are a few examples that come to mind.

1) The Nature of Progress

What jumps at me from reading stories from the 80s and 90s is how much progress society has made. Of course, we could always argue about the rising inequality, inflation, and many other valid concerns plaguing our current reality. Yet, in the grand scheme, empirical evidence shows that the quality of life available to the average person living today is higher than what was obtainable for even the wealthiest people in the past.

Take this entry from a 16th-century surgeon suffering from Scurvy [a disease easily treated by Vit C!] for example:

Or take a minute to examine how physicians diagnosed Diabetes in the past:

While things are not perfect now, I believe we have better quality problems than past generations. But what exactly makes a problem “better”? I propose three criteria:

Agency: How much control we actually have over the outcome.

Complexity: Whether it's a survival issue or an optimization challenge.

Growth Potential: What solving it lets us do next.

Contrasting the view from the past against the scenery of our modern-day lives, it’s suddenly clear how much we've upgraded our quality of problems. This evolution is everywhere, from medicine to god-like technology like airplanes, food processing and so many other forms of knowledge documentation and transmission.

I’d rather face the challenge of AI taking my job over the certainty of dying of preventable illnesses or being trapped in subsistence farming—even though both realities are genuinely stressful to those experiencing them.

2) Migration: Trading One Set of Problems for Another

At its most fundamental level, migration is a person saying, I'm trading this quality of problem1 for another quality of problem that I might enjoy. Might because, naturally, you can't fully anticipate the extent of what you can or cannot live with.

In theory, you think you can. But in the day-to-day trenches of negative double-digit weather, constant “could you repeat that?” requests, and convoluted tax systems, “all landscapes eventually become land as the gold of the imagination turns to the lead of reality.”

When viewed through this lens, you start to understand [at least I always have] that migration is not some catch-all solution to your problems [because to be human is to be marinated in problems2]. Instead, it's you trading one quality of problem for another that you can hopefully live with. So, the question should not be, should I migrate [to the UK, US, or (insert whatever place)]?

Rather, you should ask: What country’s quality of problems do I find most compatible? Maybe that might save some disillusion down the road.

3) A Species in Collaboration

There's a Steve Jobs quote I like, and it goes something like this:

My interpretation of this quote is that everything around us resulted from a collaboration of efforts, an idea Twitter user John Collison aptly sums up when he says the “world is a museum of passion projects [built by others].”

When you really think about it, we're all just working on group projects with the past dead and the future not yet born. I have very little evidence to support my facts, but I haven't heard of other species with the sophistication of knowledge documentation, transmission, and collaboration we have, which gives us interesting advantages in the long term3.

Therefore, extending my definition of progress in point 1 above, I see "leaving the world a better place" as leaving the next generation with better-quality problems4. I also believe that everyone5 has a role to play—no matter how small or insignificant they may think—in making this possible because we're all collaborating with each other, one way or another.

As the popular Zulu saying goes, Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu: a person is a person because of other people.

4) Gratitude

I'm proud of the next line; even if in a few years, I might consider it clever-sounding nonsense. But the general idea is that the quality of your problems is a lag indicator of your blessings.

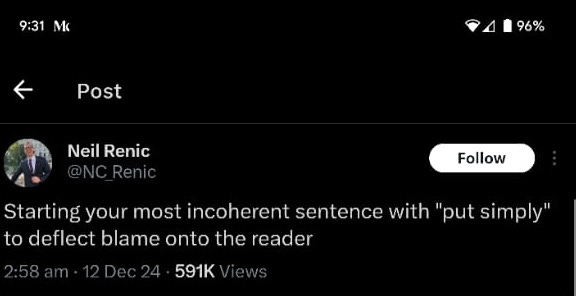

Put simply6: Whatever quality of problems you have7, when unpacked, can be traced to whatever blessings, however small they may seem, you have.

Shoveling snow? You probably own a house or at least have a roof over your head.

Nagging parents? You have parents who are alive—and I'm assuming well enough—to nag you.

Laundry? It means you have clothes. Etc.

Again, life is not all bursts of sunshine and rainbows, but I find this mindset allows reframing, as one of my friends says. And trust me, reframing is a super powerful tool.

Here are two reframes that have stayed with me.

Profound:

And hilarious:

Serious talk: When you reframe, you have the agency—“the capacity to do something different from, or in addition to, the events that simply happen to you”—to decide on your quality of agony. Consider this: The writer in the previously linked piece chose to write about her grief rather than trying to forget the loss of her husband, children, and parents because it was a "better quality of agony."

5) Doing What You Love

I raise the motion to change the often quoted but rarely convincing "do what you love" phrase to say, "choose your quality of problem."

A problem suggests a solution, which informs a goal, which then gives you something concrete to work toward. “Doing what you love" is endless, shapeless, and abstract, which doesn't help with staying power when the going gets tough.

I say staying power because the more time you spend solving a problem/staying in the game, the more opportunities you get to solve more problems, which, naturally, makes you better at solving that specific problem. Is this a roundabout way of saying that choosing the quality of your problem allows you to achieve tenure?

6) Parents vs. Kids

I believe that at the heart 8of the tension between parents and kids is their differing definitions of quality of problems. A parent solves what was a problem for them growing up, and in doing so, they upgrade their child's quality of problems. Then, the parent, rightly confused, wonders why the child is struggling or is baffled at what the child considers a problem.

Half the time, a flustered parent wonders [to one in particular or maybe to God]: is this your struggle?

Maybe a different or perhaps more kinder pov is understanding that what everyone considers a problem is relative to their starting point. As in, if you grew up like my friend9, without constant electricity, good roads, or even a coherent president, seeing these things feel like you’re in heaven. Conversely, if these were your starting point, you'd probably want heated sidewalks and other things of that nature.

Let’s zoom out some more to see the difference in expectations between generations using actual data and personal experience:

Grandfather (1940s):

Infant mortality rate: 140 per 1,000

Primary concern: basic survival

Success metric: alive children

Father (1960s):

Infant mortality rate: 40 per 1,000

Primary concern: getting an education

Success metric: stable career (true story: my dad once laughed at me when I said I was searching for career satisfaction, saying, “Do you think I enjoy being a doctor 😂”💀)

Me (1990s):

Infant mortality rate: 4 per 1,000

Primary concern: work-life balance

Success metric: self-actualization

7) Being Selfish About What You Care About

There's a quote from a Johnny Harris video that goes something like this: “[Human beings] have Paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions, and God-like technology."

Zoom in one second on the paleolithic emotions part, and we can draw a straight line to the culprit—the human brain. The human brain, despite its impressive power, has clear constraints. Neuroscience research shows our working memory can only handle about 4-7 items simultaneously (miller's law). When we try to solve every problem we see, we're fighting against our cognitive architecture.

Here’s an explanation of the human brain I really like:

And here's a take that’s both hilarious and valid:

My interpretation of both images above is this: cognitive real estate is super expensive, so you need to be militant about the structures [read as problems] you allow to take root in them. Pick the problems you can do something about and tune out the rest. The human brain was not created to cater to the amount of noise we have in today's world.

I understand that this is a difficult ask, and in some cases, you might be asking, what of the xx and xxx big problems that are plaguing the world?

Friendly advice: Pick a problem you can do something about or improve, even if it's by 10%, and shut out the rest. It doesn't have to be a sexy problem or anything major; it just has to be something you can do something about. As Richard Feynman wisely said, no problem is too small or too trivial if [you] can really do something about it.

8) The Future Is Flexible

In my experience, the biggest challenge with planning for my future self is that I always fail to account for all the qualities of problems that come with that version of me. Of course, I plan as best as possible and this is not an excuse not to plan, but I quite often find real-world experiences I never anticipated.

Stuff like lifestyle creep, burnout, apathy, change in taste or resilience, etc.

All of these continue to surprise me and it's something I constantly laugh at. My current self laughs at my old [teenage] self for being so wide-eyed about things like xx amount solving all my problems, or well-worn lines like "just graduate from University & you'll be fine."

I raise these examples tongue-in-cheek, but the central idea still holds. Sometimes, when I catch myself naively thinking that any amount of money can completely solve all my problems, I watch this clip from Billions as a much-needed, quick-handed, whip-lash reminder.

9) Life Is So Rich

I spent a large part of my teenage years [sorry, Kehinde!] and the early parts of my adulthood [sorry, ex-managers!] complaining about the many ways the world was messed up and unfair.

Naturally, this meant I was constantly angry, moody, and a whole list of other unpleasant attributes. But somewhere along the line—maybe from real-world experience or that stint working at a general hospital—I started seeing how pointless all that complaining was. It didn’t fix anything, and worse, it made me feel even more stuck.

That shift in perspective didn’t emerge overnight. Around the same time, I came across a Murakami quote that put my dilemma into words:

“All we can do is breathe the air of the period we live in, carry with us the special burdens of the time, and grow up within those confines.”

Then, almost on cue, I ran into the Tolkien quote below:

So, I decided to spend less time complaining and focusing more on what was in my control. In a sense, I guess you could say that I made peace with the quality of problems in my life.

Reader, the difference in my quality of life made me wonder why I didn't adopt this mindset earlier. It's not perfect, but I like this version of myself way better than previous versions.

These days, whenever I feel the dark clouds of complaints and minor frustrations bubbling up, I remind myself of two things:

There's progress [read as better quality of problems], and I list them individually, like in point 1 above.

"There may be more beautiful times, but this one is [uniquely, weirdly, and even if occasionally frustrating] ours.”

[Emphasis mine]

I find that migration or leaving familiar/comfortable spaces is a good way to escape the region beta paradox. However, as a Twitter user wisely reminds us, this only works if there's some fire already in you. Otherwise, how else do we explain that African countries regularly experience several [man-made] crises yet... [Astagarfullah]

Recommended reading: Travel as a cure for discontent—probably different contexts, but I believe that the spirit applies.

This also introduces a risk: as knowledge compounds, so do unintended consequences. The same technological advancements that eradicate disease can create global surveillance states. Progress is real, but it requires vigilance to ensure the quality of problems we pass down is actually better rather than just different.

Again, I understand not every problem truly gets *better*—some just mutate. Inequality existed in feudal societies, and it exists now in different forms. Psychological stress isn’t new, but modern life has created its versions of it. So the real metric of progress isn’t just problem replacement, but whether we’re actually improving our ability to deal with these problems.

I increasingly realize that in many cases, the messenger is as important as what is said, which is a roundabout way of saying that you might just be the voice that clicks in the way someone likes to be spoken to or fed information. So, you should always act as a primary source, providing firsthand information about a topic or event from your POV.

Steelmanning myself here: Not every problem has a hidden blessing. Some struggles—chronic illness, systemic oppression, deep grief—don’t become “better” just because we change our perspective. I think we just learn to live with/accept them better. I raise this to say that while gratitude is super useful, it also has its limits.

Another tension is that wisdom can only be earned by experience, which might be frustrating for parents who want to supercharge their child’s learning.

Friend is me. I am friend.

Thank you Aronkus for the editing rigour you brought into the last version of this essay to help curb [some of] my meandering.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this. I have so many notes and hopefully when we catch up next, I’ll offload them. The migration part is so surreal and I’ll be reflecting on that deeply.

PS: I love love how you introduced each quote and reference - I’ll be stealing that lol

You’ve helped develop a half-formed thought that’s been on my mind for a while now. I thank you for that; I’ll have to come back to read this again.